Rihito Kimura

It is quite clear that legislation is an instrument of social control that leads societies to change the function and system of their traditional ideas and behavior (Schubert 1975). Law is not identical to moral regulation and control, but legislation requires moral support if it is to be adjusted to the political, cultural, and economic framework of particular societies which actually produce new legislation (Miller 1979).

__Due to the rapid development of biomedical science and biotechnology, as well as strong interest in their application to the public's interests in health, several achievements in the form of new legislation have been made by health experts and bureaucrats concerning public health issues (Brahms 1990).

__In Japan, immediately after World War II, some of this legislation came into being followed rapid changes in society. In this paper I shall adopt the framework of past and present Japanese legislation, and consider prospective legislation in the form of case studies to clarify the basic jurisprudential issues that arise due to advances in modern genetics.

These topics are:

1. eugenic protection legislation and mental disabilities;

2. maternal-child health legislation and genetic screening; and

3. health information legislation and human genome analysis.

| Eugenic Protection Legislation and Mental Disabilities |

The Eugenic Protection Law (Yusei Hogo Ho) was promulgated on July 13, 1948, and remains in effect today. It took as its model the National Eugenic Law (Kokumin Yusei Ho) enacted in 1940. The enforcement of this National Eugenic Law rested on a clear policy of increasing Japan's population, in its quality and quantity, to serve as a base of state power under the influence of a wartime, military-oriented government bureau.

__This legislation was influenced by the powerful ideology of the worldwide Eugenic Movement (Suzuki 1983). The aim of the legislation was to develop and promote a future Japanese population by employing eugenic screening processes to prevent an increase in the number of genetically inferior descendants, including physically and mentally impaired descendants. The health of mothers was not much taken into account in this National Eugenic Law, although the words "Umeyo Fuyaseyo" (Be fruitful and multiply) became a national slogan for a state policy supported by the military regime in power during the war years, 1941-45 (Kimura 1984a, 1987).

__After the war, due to a fundamental change in state policy - in transition from a military regime to a democratic political system based on a new constitution (Nov. 3, 1946) - and in the midst of social and economic confusion as well as an enormous population increase, the old National Eugenic Law (1940) was abolished and the new Eugenic Protection Law (1948) was enacted. Even though drastic political changes occurred in Japanese society, which led to the formation of a law relating to the health of the people, the term "eugenic" remained. Yet this new legislation had a completely opposing objective: to decrease the Japanese population by permitting abortion without prosecution only in cases of particular medical and social indications provided in article 14 of the Eugenic Protection Law. Indeed, even now, abortion remains illegal in Japan (Chapter 29, art. 212-216, Japanese Criminal Code, 1907).

__Controlling the size of the Japanese population was also the policy of the Occupation Forces under the command of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur and his staff. The Eugenic Protection Law was proposed by a Japanese congressman, Dr. Ohta, who had been an advocate of family planning practices since the 1930s; however, there had been a good deal of pressure from the National Resource Section of the General Headquarters to enact this new legislation, and various comments concerning this proposed law appeared in official documents of the government (Kimura 1984a).

__Thus the new Eugenic Protection Law was simply regarded as an abortion law rather than a eugenic law by medical professionals and the laypublic. One of the important articles in this law requires that there be no legal justification for abortion due to a genetically defective fetus. There has been a proposal to amend this article, but it has not yet been adopted.

__The purpose of the Eugenic Protection Law is stated in Article 1:

__"The purposes of this law are to prevent the birth of inferior descendants from the eugenic point of view, and to protect the life and health of the mother as well."

__The Eugenic Protection Law actually serves as a law for eugenic and maternal protection by applying the methods of "eugenic operation" (Article 2) and "artificial interruption of pregnancy" (Article 2-II). In this law the term "eugenic operation" refers to any surgical operation that makes a person unable to reproduce without removing the reproduction glands, as prescribed by Order. "Artificial interruption of pregnancy" refers to the artificial discharge of a fetus and its appendages from the body of the mother during the period when a fetus is unable to remain alive outside the body of the mother. (This particular time period ends around the 22nd or 23rd week of gestation.)

__It is quite important to note that the original text of the Eugenic Protection Law included no provisions permitting economic and social reasons as justifications for an artificial interruption of pregnancy. In 1949 the law was amended to remove the rigid provisions concerning maternal protection, with the qualifying statement that: "if the mother's condition is seriously endangered by economic reasons..." In 1952, another amendment was introduced to abolish any investigation by the District Eugenic Protection Commission and to give physicians the final authority to decide when to artificially interrupt a pregnancy, as well as to provide women a program for practical guidance in birth control and family planning.

__The Eugenic Protection Law has three major elements:

1. articles relating to the process of eugenic operations

2. articles relating to the conditions for having artificial interruptions of pregnancy

3. articles relating to practical guidance for birth control methods and family planning.

__According to the Eugenic Protection Law there are two forms of "eugenic operation." One is called the discretionary eugenic operation (Article 3), which the physician may perform at his discretion after he obtains the consent of the woman and the spouse. There are five clear indications for this operation:

1. the person in question, or the spouse, has hereditary psychopathia, hereditary physical disease, or hereditary malformation, or the spouse suffers from mental disease or mental disability;

2. a blood relative, within the fourth degree of kinship of the person in question or the spouse thereof, has hereditary mental disease, hereditary debility, hereditary psychopathia, hereditary physical disease, or hereditary deformity;

3. the person in question or the spouse thereof is suffering from leprosy, which is considered to be contagious for the descendants;

4. a mother whose life is endangered by conception or by delivery;

5. a mother who actually has several children whose health condition is feared to be seriously affected by any future delivery

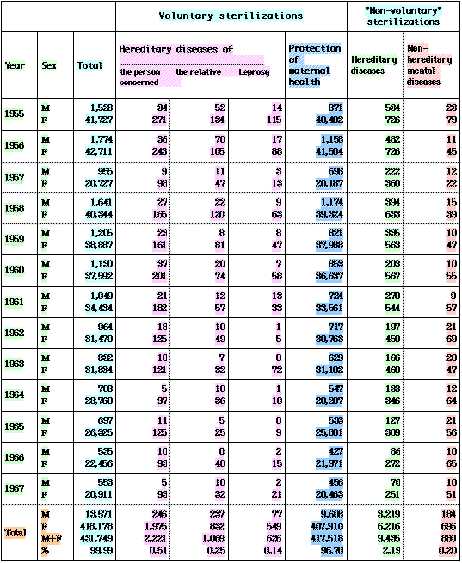

__The second method is called the non-voluntary eugenic operation. If, as the result of an examination, the physician discovers one of the diseases enumerated in Table 1 and recognizes that a eugenic operation is necessary for the sake of the public interest to prevent the inheritance of the disease, he is required to report this finding to the Prefectural Eugenic Protection Committee (PEPC).

| Table 1 |

1. Hereditary Psychosis

__Schizophrenia

__Manic-depressive psychosis

__Epilepsy

2. Hereditary mental deficiency

3. Remarkable mental psychopathology

__Remarkable abnormal sexual desire

__Remarkable criminal inclination

4. Remarkable bodily illness

__Huntington's chorea progressiva

__Hereditary spinal ataxia

__Hereditary cerebellar ataxia

__Progressive muscular atrophy

__Dystrophia musculorum progressiva

__Myotonia

__Congenital musculorum atonia

__Congenital cartilaginous malgrowth

|

__Leukosis

__Ichthyosis

__Multiple soft neurofibroma

__Sclerosis nodosum

__Edidermolysis bullosa hereditaria

__Congenital porphyrin urine

__Keratoma palmare et plantare

__hereditarium

__Atrophia nervi optici hereditarium

__Pigment degeneration of retina

__Achromatopsia

__Congenital nystagmus

__Blue sclera

__Hereditary dysacousia or deafness

__Hemophilia

5. Intense hereditary malformation

__Rupture of hand, rupture of foot

__Congenital defect of bone

|

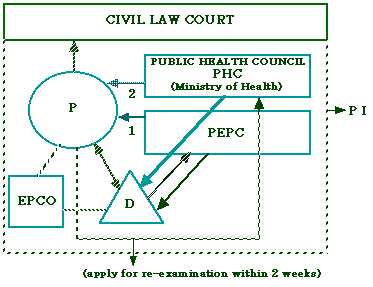

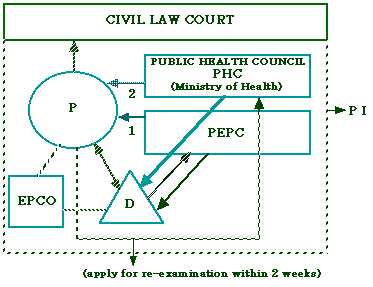

__In cases of eugenic operations and sterilization, there are fundamental and crucial elements which are closely related to the protection of the rights of the individual (Brakel and Rock 1971; Wexler 1980). This is why the Japanese Eugenic Protection Law includes several articles that provide for appeals to challenge the first decision taken by the PEPC, and the second decision taken by the Public Health Council (PHC), and finally open the way for the initiation of a lawsuit in civil court, as provided in article 9 (see Fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 1. Compulsory eugenic operation procedure and system in Japan according to the Eugenic Protection Law of 1948. P, person (spouse, guardian, parents, etc.); D, medical doctor; P.I., public interest; PHC, Prefectural Eugenic Protection Committee (10 members); EPCO, Eugenic Protection Consultation Office. |

__Very few of these non-voluntary operations are being performed (see Table 2), and these are mainly requested by parents, guardians, or spouses. Such requests are made, as a matter of fact, due to eugenic considerations on behalf of a particular person. Non-voluntary operations are usually not performed if the person concerned brings the issue to civil court, because the majority of Japanese tend to think that courtroom resolution of these conflicts might not be socially appropriate (Kawashima 1963; Kimura 1988a).

__One can raise a serious question concerning the fundamental ideological premises of the Japanese Eugenic Protection Law. One of the most problematic articles in this law concerns providing eugenic operation to patients who are in different categories than are indicated in the attached list (Table 1) of the Eugenic Protection Law, e.g., mental illness. Article 12 states:

| A Physician may in regard to a person who is psychotic or mentally deficient (other than by hereditary causes mentioned in item 1 or item 2 of the Annexed List) obtain consent from the person who is responsible for protecting the patient under the provision of article 20 (in cases where the guardian, spouse, person exercising parental authority, or the person under obligation to sustain becomes person obligated to protect patient) of the Mental Hygiene Law (Law No. 123 of 1950) or article 21 (In the case where the mayor of the city or the chief of the town or village becomes the person obliged to protect the patient) apply for investigation concerning the reasonableness of performing eugenic operations to PEPC. |

__Article 13 provides that if an application to the PEPC is made, PEPC shall investigate whether or not this patient suffers from a psychosis or mental deficiency based on Article 12, and whether or not the performance of a eugenic operation is necessary to protect the patient. Thus the PEPC decides the reasonableness of performing the eugenic operation and informs the applicant and those who give consent (provided in Article 12).

__Even though there are legal mechanisms to protect the rights of mentally ill patients, there have been quite a few cases concerning violations of these rights in various institutions for the mentally ill. Observations and documented reports, as well as recommendations by an International Commission of Jurists in Geneva together with a nationwide campaign for the reformation of this situation in Japanese mental hospitals, led to an open debate on these issues (International Commission of Jurists 1985). As a result, an amendment to the Mental Hygiene Law was passed in 1987. This shows the grave importance of international cooperation concerning changes in the traditional system, not only regarding mental diseases but also in the area of policy. Today, the people still need much more information and better education concerning mental and genetic diseases (Hirano 1987, Grostin 1987).

| Maternal-Child Health Legislation and Genetic Screening |

In Japan, there are several genetic screening programs for newborns. The Maternal-Child Health Law (Boshi Hoken Ho) of 1966 was enacted for the maintenance and promotion of the health of mothers, neonates, infants, and children.

__One of the unique practices based on this law (Article 16) is the issuance of a Maternal-Child Health Notebook to all of those who register at local offices or health centers governed by local authorities. Any woman who becomes pregnant informs the local office (Article 15) to receive various medical and health services, which she must then record in her Maternal-Child Health Notebook each time she receives these services (Kimura 1986).

__There is no precise provision regarding a genetic screening program under the Ministry of Health and Welfare or local government. However, a practical ordinance from the MHW gives administrative and legal justification for a genetic screening program which was initiated by health experts and bureaucrats at the level of central and local government (Ohkura and Kimura 1989).

__In 1977, the mass-screening tests for inborn errors of metabolism were performed on only 29.2% of all newborns; in 1984 this percentage grew to 99.6% (Health and Welfare Statistics Association 1986). These screening programs for inborn errors of metabolism include PKU, maple syrup urine disease, homocystinuria, histidinemia, and galactosemia. The screening program for cretinism began in 1979, and for neuroblastoma in 1985.

__These practical medical and health services are justifiable given the present legal framework. However, the detailed information provided for these screening practices, and the final endorsement by the laypublic, should be considered seriously in the health education process in the community, in local health centers, and in local schools. The initiative taken by the central and local governments on these issues of mass screening has delicate implications, relevant to an individual's health and the importance of protecting the privacy of genetic information. In this sense, even though there is a very positive side to the promotion of maternal-child health based on legislation, the practical requirements that all pregnant women file a report with the local authorities might cause some uneasiness for those who are seriously concerned about the real meaning of privacy rights (Kimura 1984b).

__The positive reaction of Japanese pregnant women to this government ordinance reveals that the benefits of receiving genetic screening could also be recognized as a right of pregnant women to receive services from the government (Ohkura 1984).

| Health Information Legislation and Human Genome Analysis |

There is growing concern regarding future research on, and the application of, human genome analysis. The information acquired from human genome analysis could radically change the traditional notions of medical and health services, since some illness situations will be predictable beforehand. Genetic information about ourselves could change our lifestyles, behaviors, habits, etc. (Kimura 1990a).

__Health information legislation designed to protect personal privacy has not yet been proposed in Japan. However, such legislation should be passed before scientific and technical "fixes" become available; otherwise, violations of privacy could occur too often. Schools, employers, insurance businesses, and future spouses might claim that it is necessary for them to obtain genetic information to protect the persons concerned. What criteria should be established to give or not give genetic information to these people and organizations?

__The control and maintenance of genetic information in Japan has already begun, e.g., the registration of all pregnant women. There is no guarantee that personal privacy will be protected, even though there are some articles in the law that provide penalties for disclosure of particular information acquired by health professionals in the process of conducting their services (Kimura 1990b).

__Additional integrated legislation concerning the private nature of health information (particularly as it relates to the human genome) is clearly required.

__International guidelines are needed prior to initiating new legislation in various nations. The centralization of genetic information would give those in control enormous power over a population, and this could lead to rather serious consequences.

__"The right to be different" in pluralistic, multi-cultural nations in the contemporary world should be a fundamental principle in jurisprudence that must be maintained as a basis for future legislation.

Genetic manipulation for the enhancement of the body or abilities in a direct way should not be recommended and might be prohibited by legislation. However, genetic manipulation for the cure of disease and suffering would be justified bioethically and legally. Public debate on these issues of genetic manipulation would be extremely helpful, including contributions from various disciplines such as jurisprudence, bioethics, religion and genetics. Open communication between experts and the lay public should be a basic factor in making public policy and regulation relating to genetic health issues (National Institutes of Health 1990; Kimura 1988a).

Brahms D (1990) Human genetic information: the legal implications. In: Chadwick D, et al. (eds) Human genetic information: science, law and ethics. Wiley, New York, pp 111-118

Brakel SJ, Rock RS (1971) The mentally disabled and the law. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Gostin L (1987) Human Rights in Mental Health: Japan. The Harvard University/World Health Organization International Colaboratoring Center for Health Legislation, Boston

Health and Welfare Statistics Association (1987) The trends of national health HWSA, Tokyo, p 104

Hirano R (1987) Psychiatry and law (in Japanese). Yuhikaku, Tokyo

International Commission of Jurists (1985) Human rights and mental patients in Japan. ICJ, Geneva, pp 80-86

Kawashima T (1963) Dispute resolution in contemporary Japan. In: von Mehren AT (eds) Law in Japan. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 41-59

Kimura R (1984a) The roots of family planning and its perspectives in Japan. Jpn J Nurs 48 (11): 1301-1304

Kimura R (1984b) The meaning of gene therapy. Jpn J Nurs 48 (9): 1061-1064

Kimura R (1986) Caring for newborns. Hastings Center Rep 16 (4): 22-23

Kimura R (1987) Bioethics as a prescription for civic action: The Japanese interpretation. J Med Philos 12: 267-277

Kimura R (1988a) Bioethics in the international community. In: Bernard J, et al. (eds) Human dignity and medicine. Elsevier, New York, pp 191-196

Kimura R (1988b) Bioethical and socio-legal aspects of the elderly in Japan - with special reference to life-sustaining technologies. In: Institute of Comparative Law (ed) Law in East and West. Waseda University Press, Tokyo, pp 175-200

Kimura R (1990a) Religious aspects of human genetic information. In: Chadwick D, et al. (eds) Human genetic information: science, law and ethics. Wiley, New York, pp 148-166

Kimura R (1990b) The project for human genome analysis and bioethics, J Human Sciences 3 (1) Waseda University. Advanced Research Center for Human Sciences, Tokyo

Miller AS (1979) Social change and fundamental law. Greenwood, Westport

National Institute of Health (1990) Governmental oversight and public participation. NIH, Washington, pp 6-7 (Gene therapy for human patients, information for the general public, part 2)

Ohkura K (1984) Clinical genetics (in Japanese). Nippon Ijishinpo Sha, Tokyo

Ohkura K, Kimura R (1989) Ethics and human genetics in Japan In: Wertz D, Fletcher JC (eds) Ethics and human genetics: cross-cultural perspective. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 294-316

Schubert G (1975) Human jurisprudence. University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu

Suzuki Z (1983) Eugenics in Japan (in Japanese). Sankyo Shuppan, Tokyo, pp 99-186

Wexler N (1980) "Will the circle be unknown?" Sterilizing the genetically impaired. In: Milunsky A, Annas G (eds) Genetics and the law II. Plenum, New York

Do you have anything to say about the contents of this page?

Do you have anything to say about the contents of this page?

Please send your opinion to

Do you have anything to say about the contents of this page?

Do you have anything to say about the contents of this page?